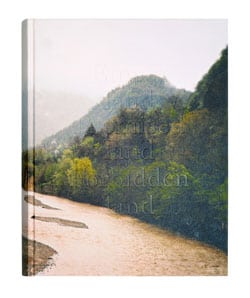

The Sochi Project

The world has long harboured a fascination with Russia: the vastness, the politics, the wealth, the poverty, its resources, diversity, monotony, and spirit. From Kaliningrad in the west across the Eurasian landmass to Ratmanov Island in the Baring Strait, the country is difficult enough to comprehend for it’s natives – but what about a foreigner?

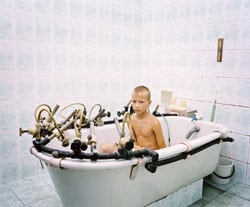

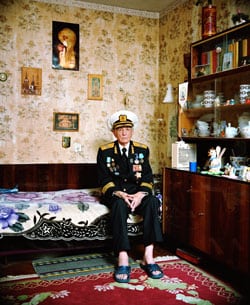

Rob Hornstra is that outsider. He began photographing Russia as a student travelling from Netherlands and has continued his task ever since. Characterised by engaging rawness, his images and fresh approach has forced a re-appraisal of a nation in flux. However, publishers were initially cold to Hornstra’s images of post-Soviet Russian life and rejected his book proposals. This forced him to self publish in order to getting his photographs seen by the wider public. He’s never looked back.

Hornstra launches his limited edition Sketchbook Series this autumn under umbrella with writer Arnold Van Bruggen. We caught up with him to find out more…

New European Economy You have a wide ranging interest in subject matter based around people and places, but you have made a long term commitment to photographing Russia. What drives your interest (geo-political/socio-political?) and how do you maintain an editorial focus on such a vast country?

I started working in Russia in 2003 for my graduation project. I was – and still am – fascinated by this country. On a first glance you think it is a little bit similar to Europe, but the more often you go there, the more you experience the differences between Europe and Russia. Every time I go back, I discover new topics and new storylines, which I would like to follow. Besides that I am not the type of person who likes travelling, or who likes to go to many different countries. Instead I prefer working somewhere for a longer period to dive deeper into the subject. I can imagine that I will stop working in Russia after the Olympic Games and will move on to another country or continent to work there for ten years. We will see.

Why did you choose to document Sochi?

Rob Hornstra In 2014, the Olympic Games will take place in Sochi, Russia. Never before have the Olympic Games been held in a region that contrasts more strongly with the glamour of the Games than Sochi. Just 20 kilometres away is the conflict zone Abkhazia. To the east the Caucasus Mountains stretch into obscure and impoverished breakaway republics such as Cherkessia, North Ossetia, Chechnya & Dagestan. On the Sochi coastline old Soviet sanatoria stand shoulder to shoulder with the most expensive hotels and clubs of the Russian Riviera.

Between now and 2014 the area around Sochi will change beyond recognition. The extreme makeover is already underway; poverty-stricken resorts are disappearing at high speed from the partly fashionable, partly impoverished seaside resort of Sochi. Thousands of labourers from across Russia and abroad live in prefab accommodation in order to have the stadiums, hotels and modern infrastructure finished on time. Helicopters fly backwards and forwards with building materials. The economic crisis is glossed over as much as possible. At the same time, billions are being invested in the Northern Caucasus to appease the local population in order to eradicate extremism and violence. The Putin government tries to build 5 new ski resorts in Chechnya and the other republics. At the same time, corrupt regimes who don’t care about human rights are being kept in place in these republics, as long as they manage to quiet down the population.

All these contrasts provide food for many stories. That’s what we’re doing, mapping the region before the Olympics will be here. And when people go on the internet during the games, they will find our stories and they can read on the background of this region, the context of these Games, instead of being fed a folkloristic, shiny happy image of Russia and its government.

How has it changed since you’ve been visiting – what are the positives and negatives of the developments you have witnessed?

Sochi is undergoing a huge change. Almost everything is being built from the scratch. The airport, seaports, train stations, tunnels, highways, modern luxury hotels, it’s incredible. At the same time, Russia is working hard to fasten its grip on the region. It more or less occupies the former Georgian provinces of Southern Ossetia & Abchazia after the Russian-Georgian war in 2008 and intensifies the war against terrorism and separatism in the region. Russia is investing billions of dollars to prevent the worst threat to the Games: a domestic-born terrorist assault.

What is the purpose of the project – do you hope to make changes or do you take a more passive approach?

We hope that we provide the glamour and glitter of the Games – the most expensive games in the history of the winter games – with a lot of substantive journalistic context. With our books, stories and photoseries our audience will become accomplished witnesses

You have successfully self-publishing several books on Russia, who buys them and why were publishers slow to understand the demand?

Most of my books are bought by people who are interested in photography or in documentary stories (or a combination). Photo books are expensive to produce, so they are also expensive in sales. That’s one of the reasons why not many people buy these books. A print run of 1,000 copies is common these days.

Nevertheless, the idea is that my books (our books within The Sochi Project) are accessible to a much wider audience on the Internet (for free). www.issuu.com/borotov. And it works. For example the first annual publication of The Sochi project (‘Sanatorium’) is already viewed around 60,000 times, thanks to people who embed this story in their website.

There is by the way also a vivid trade in photo books. Part of my books is bought by people who invest in photobooks. The photobook business has become a kind of alternative art market. A good photobook does not loose its value and many books become even more valuable.

Regarding your second question, I am not sure if publishers were slow to understand. The fact is that I never approached a publisher and a publisher never approached me.

How do your own commercial principles – which were bourn of necessity – sit with the corporate and state driven commerciality that’s happening in Sochi?

They have nothing to do with each other I guess? Sochi is a hypercommercialized place but at the same time, many Russians and all the other nationalities who live there have a hard time getting around. It’s a diverse place, as is the whole of Russia. Russians have a huge capability of surviving. Every family in Russia and the former Soviet Union is touched by the great famine of the 1920’s and 1930’s and the great terror of the 1930’s and 1940’s. They have a way to manage crises, as you could see in the 1990’s as well. Without any money or economy they managed to survive. The idea that private individuals donate money to our work may seem like a strange idea to Russians, but I think the aspect of us finding ways to get around will sound familiar to them.

What percentage of sales goes to Russia? How is your work received there?

Unfortunately not many Russians seems to be interested in my work. Of course I have a western orientated view on Russia and I do not see a reason to hide this. For example in the next month we are publishing a book about singers in restaurants along the beach line. I am convinced that not one single Russian photographer would ever think about making a series on this topic. Although the subject perfectly shows how a deeply rooted Russian tradition goes hand in hand with the city’s new capitalist glamour.

Do we have a voyeuristic view of developing countries, or do you find Russians themselves like to analyse their changing society?

Every Russian has ideas about Russia, about the government and economy. There are thousands of Russian blogs who write about Russia. Russian photographers and writers alike roam the land in search of stories. But every country on earth should be covered by locals as well as by foreigners. I always like to read foreign-made stories about the Netherlands. They are usually more concise, they dare a more genrealistic approach. And of course, all writers and photographers should be voyeuristic. For us, to write and photograph a developing country – or better a country in transition – makes it the more interesting because of the huge contrasts we find. But we could use the same approach in documenting the Netherlands, Germany or the United States.